skip to main |

skip to sidebar

Greeting’s everyone, here is my final poster abstract on the feathered serpent. Approved submissions will present their visuals during the 79th Annual Meeting of the SWAA. Although the deadline for revisions has passed I am still seeking feedback to prepare for the dialogue portion.

Monuments of the Feathered Serpent of Mesoamerica: Early Formative to Postclassic…

By Santiago Andres Garcia

California State University, Fullerton

The feathered serpent of Mesoamerica is a multifaceted narrative periodically discussed and only recently given consideration in the historical development of Mesoamerica. More than just a symbolic figure of mythology, it can be interpreted as a diffusionary model of interdisciplinary beliefs that aided in the rise of early cultures and societies. Furthermore, the feathered serpent represents the early to late convictions shared by both the commoner and elite ranks of Mesoamerica. The monumental archaeology of the feathered serpent documents this sentiment and the transitions between people and places. It is evidence of a phenomenon that occurred in the Early Formative period (1200–900 B.C.) and continued onward through much of the Postclassic period (A.D. 900–1400). Presented in a pictographic manner, Monuments of the Feathered Serpent of Mesoamerica: Early Formative to Postclassic… is an iconographic study of the stelas, facades, and pyramids associated with the feathered serpent of Mesoamerica. Such a visual will allow us to better comprehend the holistic nature of the feathered serpent, as it spread beyond borders, from one region to the next. In hindsight, it pulls from a mentalist perspective and further invites the dialogue required to devise new orientations, and future studies relevant to the topic of the feathered serpent.

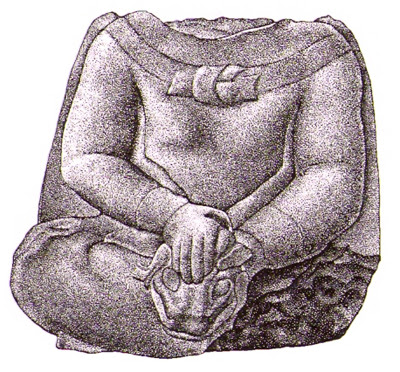

* Monument 47 from San Lorenzo. Likely a shaman (since its taming a snake), definitely a person of status suggestive by the cape and knot “bowtie” it’s wearing. The iconography of both Monument 47 and Monument 19 believably set the standard for the inception of feathered serpent imagery. Both monuments depict a human body, a serpent, and most noteworthy holy regalia. Combined they may suggest the advent of a feathered serpent cult or political party affiliated with a feathered serpent. What I find to be worthy of pronouncing is that same monumental assemblage, including the iconography, will continue to be contemporaneous with the development of later Mesoamerican cultures and societies.

* Monument 19 from La Venta.

“Borders, Boundaries and Transitions: Framing the Past, Imagining the Future”

The theme of the April 2008 SWAA conference is intended to inspire and appeal to anthropologists of diverse interests. The idea of borders can be used as a metaphor for any number of anthropological undertakings that focus on the past, the present and even the future. We look forward to papers, posters and films that will creatively engage these metaphors. In the following paragraphs are just a few examples.

The trope of borders and transitions can be used throughout every subfield of anthropology. When we look to our human past, some of our most important questions ask when various evolutionary transitions occurred, as well as how, where, and why. Transitions leading to speciation, boundaries between species, and more recently, similarities and differences in genetic makeup are all “border issues” of paleoanthropology. Some of the classic inquiries of archaeology include the transition to domestication and the rise of cities and states. In academia, we contest the boundaries and borders of our respective paradigms, theoretical frameworks, and epistemologies.

People often ask me why I named this site Where are you Quetzalcoatl… Well, for a long time I went penniless learning everything possible about Quetzalcoatl. I won’t get into details but it was one of those journeys that when you return from, everyone is mad at you, even though your intentions were good. Then to make things worst you begin to question yourself, has that ever happened to you? Anyhow, in appreciation for the time spent (and being spent) I named this site Where are you Quetzalcoatl…

Quetzalcoatl was one of Mesoamerica’s principle deities, or gods, also referred to as the feathered serpent. An acceptable label since Quetzalcoatl was often portrayed alongside a serpent or in serpent regalia. In the ancient city of Tula, Quetzalcoatl took the form of man (a priestly one), known to scholars as Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl (likely he just adopted the name). Nonetheless the subject of Quetzalcoatl is a fascinating one because its presence is seen in almost every Mesoamerican culture, from Olmec to Aztec.

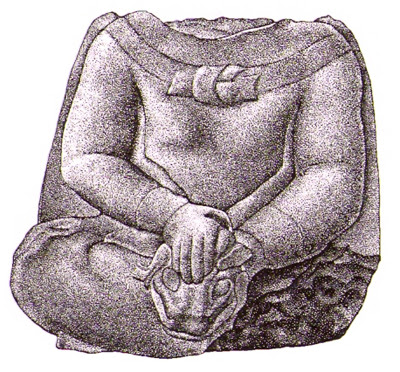

A matter to consider is the abundant pieces relevant to Quetzalcoatl, currently existing in museums throughout Mexico, without proper classification. Take for example the stone monolith of Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl (fig. 1) from the National Museum of Anthropology, Mexico City, Mexico, and the stone slab of Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl (fig. 2) from the Sala Historico De Quetzalcoatl in Tula, Hidalgo, Mexico. A close examination reveals both too be laden with similar iconography; at best, they are relevant with one predating the other. In study, the two would be worthy of interpretation, yet a meager museum record fails to support any argument(s). I know what you are thinking… Museum exhibits can be notoriously inaccurate, yet what are we to do, after all other sources have been considered? This could be an issue for the scholar looking to support his research or the enthusiast looking for a proper interpretation.

Fig. 1 Stone monolith of Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl from the National Museum of Anthropology, Mexico City, Mexico. Museum classification is vague. Picture by Santiago Andres Garcia

Fig. 2 Stone slab of Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl. This piece is from the Sala Historico De Quetzalcoatl in Tula, Hidalgo, Mexico. The piece was likely unearthed in the same area of Tula. Museum records and classification are also vague. Picture by Santiago Andres Garcia

Please note that this is not a battering of museums, museum curators, or their displays. As it turns out the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City is one of the world’s best. It provides a portal to early American ancestry and such environments should always be held in high regard. My only intention is to shed some light on the current issues puzzling us, in hopes of some clarification.

Mesoamerica is scientifically (it can be proven) one of only six, cradles of civilization known on earth. A cradle of civilization is any cultural area that developed freely without influence. Traits specific to the six cradles of civilization are language, art, and technology. Specific to Mesoamerica is the advent of maize, corn domesticated from a family of tall grasses known only to Middle America. The use of corn spurred the development of sophisticated societies such as the Olmec and the Maya. All of which had agricultural firsts, advance knowledge, and writing systems. Corn was later adopted by much of North America, and in all parts of the world for its vital consumption. The advent of corn is just a drop in the bucket of worldly contributions credited to Mesoamerica.

In the New World, Mesoamerica is truly the bread and butter of anthropological scholarship. As it did in the past, it continues to provide us with an authentic substance of study that never ceases to disappoint. As it remains important to the discipline of anthropology, it should also remain essential to our common understanding of the American continent (and for many other reasons…). One of my biggest motives in publishing this blog and this website is to bring the studies to a level that we can all enjoy. As I have mentioned before, I will keep my interpretations broad, but correct, for the sake of inviting dialogue.

Left - Teosintle grass from which corn was domesticated. Right - A mano and metate used to grind corn, still commonly used in North and South America.

Image digitized from Arqueologia Mexicana, December 2001, page 54.